What We Can Learn From Restrictive Housing Conditions in Kansas Prisons [And How to Fight Back]

By Trenton Bishop, Lansing Correctional Facility

Trenton Bishop is from Topeka, Kansas, and has been incarcerated at KDOC since 2015. He loves good conversation, good literature, and helping others.

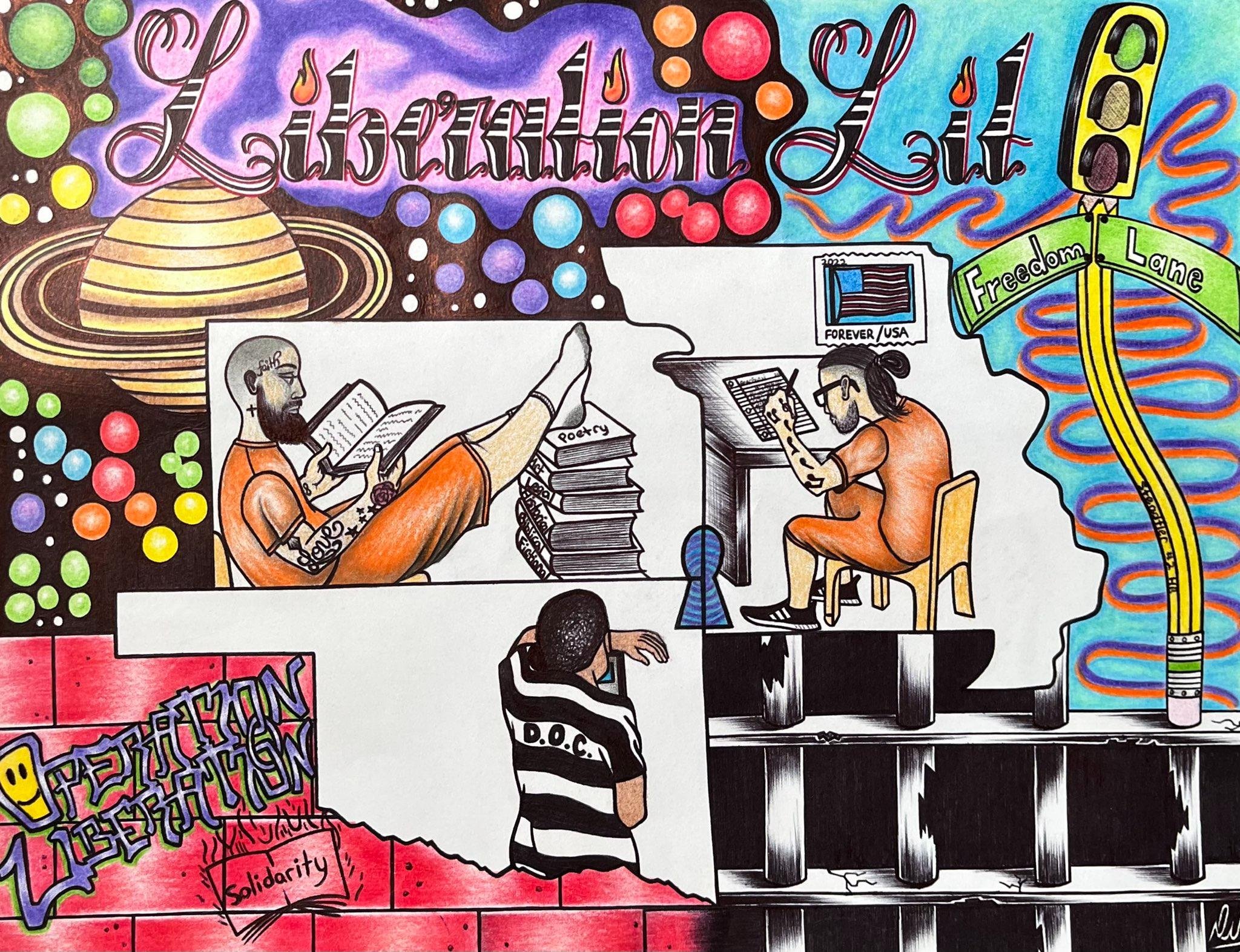

Illustration by Devon Westerfield

In This Article

-

Trenton details the situation in the A1 Restrictive Housing Pod at Lansing Correctional Facility. While many of the folks incarcerated in this pod are there for administrative segregation and have a right to the same resources and programs as general population, they are confined to their cells 23 hours a day with with little to no resources. Scroll down to read more.

-

Trenton details precisely what his days look like in Restrictive Housing. Scroll down to read more.

-

Trenton details the ways that KDOC’s internal practices have led to unsafe conditions for both residents and staff. Scroll down to read more.

-

Trent outlines possible solutions, including legislative changes and accountability for prison staff. Scroll down to read more.

-

Scroll down to read more and click here to send an email to Jeff Zmuda and KDOC in support of the people incarcerated at Lansing.

-

Scroll down to read more.

The Basics

I am in A1, a Restrictive Housing pod at Lansing Correctional Facility. We have no opportunities for recreation and little opportunity to communicate with the outside world. Over the course of the last several months, we’ve lost day room and outside yard time, including the mini caged-off “backyard” that has a basketball goal and two tables with a fence around it.

It used to be that “Restrictive Housing” did not mean our bodies were completely restricted. We had access to our day room and the yard for fresh air. Restrictive housing used to be closer to what general population is like. In general population, they walk and move. They are able to work out outside of their cells and leave their cells for meals. They go to see a doctor if they need one. Here, if we want to exercise we have to do so in our tiny cells, and if we need a doctor, they come to us. Federal case law says that prisons have to provide opportunities for exercise outside of our cells, but we have no opportunities for movement and have not tasted fresh air in over six months.

In A1, we have a mixed population, meaning while most of us are in administrative segregation, there are some also here for disciplinary segregation. Having multiple custodies makes it easier for our unit team to claim a security risk and put us on lockdown.

I have been in this pod since February of last year, and I have been in Restrictive Housing since the night of Christmas 2019. My pod has been reclassified from Protective Custody to Other Security Risk multiple times with no explanation. That makes it easier for unit team managers and KDOC administration to treat us however they want with no questions asked.

I recently found out that out of all the segregation pods, we are the only pod that cannot order any food canteen or union supply boxes. We are also the only pod where the majority of us haven’t been in any serious trouble and haven’t had a discipline referral (DR) in a very long time. We are being punished more severely for no justifiable reason.

This article is not an attempt to seek pity. It’s an attempt at understanding and accountability, an attempt to challenge those who keep the truth in the dark, and an attempt to overcome the fear of bringing truth to light.

A Day in the Life of Restrictive Housing

We do not go anywhere and we get our food brought to our rooms.

Our morning medication is around 2:30 a.m. and breakfast comes at 4 a.m. We get showers every other day, and depending on the officers (both the number of officers that show up to work and their attitudes), we either get out around 8 a.m. or after lunch. Monday through Friday, it’s most likely 8 a.m. Saturday and Sunday, it’s most likely after lunch.

Lunch is around 9:30 a.m. to 10:30 a.m., again depending on the days and the officers. Instead of a hot meal as you might get outside Restrictive Housing, we get sack lunches that consist of bread, a small bag of chips, either a cake or a cookie, and the main course alternates between either a piece of meat or two packs of peanut butters and two jellies the size of ketchup packets. Medication comes again around 2:30 p.m., and then it’s count time at 2:45 p.m.

Dinner comes around 4:00 p.m., Both breakfast and dinner come in styrofoam and lunch is sacks. I am on Religious Diet meals which have certain item switches. Instead of biscuits or rolls in regulars (or standard issue meals), I will get real bread. Instead of cake or cookies, I will get “religious cookies,” or an orange and packaged religious meat. We all also get chopped up carrots and a generic packet of chemical “Kool-Aid.”

We have fifteen minutes on the phone the same day we get showers, which are only supposed to be fifteen minutes as well. Beyond that, we are in our cells. My days are spent in my bunk, writing, reading, watching TV (which I am privileged to have), and trying to work out. On the weekends, we may get sympathetic officers that will give us more time to call home because they know what is being done to us is very wrong and that out of every pod in the compound, we are the only ones being treated like this.

KDOC’s Inconsistent Policies and Inadequate Communication

KDOC Secretary Jeff Zmuda will not even talk to any of the family members that inquire about anything that goes on in this pod, let alone what’s gone wrong in KDOC overall. All of the facility messages being sent out to pacify the families are hogwash and tilted, part of a plan to hide what is truly transpiring in each facility.

Families and residents were kept in the dark about reasons for lockdown in 2021 after violence in the facilities. Zmuda writes to families praising KDOC’s “Pathway for Success” program, which they say “invests in individuals” and “creates an environment for change and well-being,” which makes the public believe we are all recipients of these programs when we are definitely not. Zmuda has asked for feedback from family members, but does not return calls or emails.

KDOC uses a point system to decide each inmate’s custody level, basically assigning numbers to assess and predict our behavior and risk level. Personally, I have worked long and hard to lower my custody level. My custody level is eight points. The system for custody levels is 1-7 (Minimum), 8-11 (Low Medium), 12-16 (High Medium), and 17+ (Max). Custody level is important to understand because KDOC inconsistently manages its population, even based on its own system. I have stayed out of trouble to the point that until I go to a different facility, and can ask for minimum by exception, I can no longer go down any more points until I do more time. I have been on the best behavior possible. Yet, because I am in this pod—and like most of us here, not because I’m in trouble—I am being punished. Most people down here are like this: treated miserably with no justification.

The point is that I have worked on making myself look good on paper and choosing my battles with people that enjoy making our lives miserable. I had a porter (cleaning crew) job until I got fired for helping a neighbor with mental health needs with his tablet password. After I was fired, I still helped out every night with laundry and cleaning, until day rooms went from an hour out every day to every other day—to no day room at all.

The facts remain that nobody wants to work for KDOC anymore because of bad conditions on both sides. The officers are pressed into taking on longer hours and mandatory overtime, sometimes working 12-18 hours only to come back to work the next day for another 12-18 hours. This makes them irritable and more prone to mistakes. I have seen one officer’s keys stuck and forgotten in a door in our pod for almost thirty minutes before they realized they were missing. Staff shortages are dangerous and put people in unsafe working and living conditions.

With staff shortages come the need to fill posts with untrained staff, so much so that majority of the time property is closed. Visitation is closed indefinitely–and not just because of COVID but because they collapsed the post. There was simply no one available to oversee visits. A skeleton crew is running the facility and doing work that was meant for a few hundred people. Programs can’t be run right, and even the unit teams and mental health numbers are bare minimum.

According to chapter 20-101A, section IV of KDOC Internal Management Policies and Procedures (IMPP), “Administrative restrictive housing residents must have reasonable access to programs and services including, but not limited to, educational services, commissary services, library services, social services, counseling services and religious guidance.”

Even before the quarantine, programs were not given to my pod, and we have had four mental health faculty quit since I have been here. We don’t have substance abuse programs or GED classes. We’re here to do better, but we don’t have access to any of the resources that might help us in our journey. We started with little and it’s only gotten worse.

How Do We Move Forward?

KDOC claims it has no other choice but to manage us this way. When we file complaints about conditions, they say they “can’t control the pandemic,” which misses the point. There’s a lot of talk about the ways COVID has changed everything, but the reality is that these issues go back way before the pandemic. Instead of doing what needs to be done to address the problems that were there even before COVID—to and help those incarcerated to reintegrate back into society and be successful in the community—they would rather give us more time and no way to rehabilitate. They would rather leave us struggling to survive, with no tools to cope.

For example, Good Time has been a huge debate for decades in Kansas, since 1994 when it was changed to what the “new low” is now. The Prison Policy Initiative states that Good Time is: “A system by which people in prison can earn time off their sentences. States award time ‘credits’ to incarcerated individuals to shorten the time they must serve before becoming parole-eligible or completing their sentences altogether.”

Kansas Good Time is limited to "not more than 15% or 20% of time served." Compared to most states which are 30% and above, Kansas is below the national average for sentence reductions. In 2020, Kansas legislators abandoned a plan to increase earnable Good Time credits to 50% of our sentences, which would reduce the population and ease the stress on all of us.

Kansas is horrible when it comes to the court system and prison system combined. Instead of seeing people, they see profitable sacks of meat. But their mistreatment of us runs so deep that they’re even losing out on those profit opportunities they care about so much. Even from a business standpoint, KDOC could be making so much more money and have so much more profit by helping the incarcerated get educated and mentored, and by putting in real programs to help us understand ourselves, make more jobs available, and quit narrowing the work field, but they don’t.

Good Time should be at least 35% for violent offenders and 40% for regular offenders, but it goes further than that. Republican lawmakers specifically have included illegal and unconstitutional language into laws, creating illegal laws for profit and political gain, which we’ll get into in another article. The main takeaway is that the ability to legally fight in court has become twice as hard and expensive for those that have no money or understanding of the law.

Enough is enough. If people want to change and be better, why should anyone get punished for it? Those of us in Restrictive Housing are here to do better, be better, and try to get home—but the people running the system are taking away more and more of our means to be better in the first place. Why are we being shunned by those who gave an oath to protect, help, and teach us? Why are we being treated worse and worse with no justification? Things have to start changing as soon as possible.

Action Item: Demands for Jeff Zmuda and KDOC

Under the watch of Jeff Zmuda and the Kansas Department of Corrections, there is a gross mistreatment of incarcerated people, and multiple violations of KDOC’s own Internal Management Policies and Procedures. In response, Trenton and a group of folks incarcerated at Lansing are leading an organized resistance—in the coming weeks, dozens of people are submitting a version of the demands listed below as Form 9 Complaints.

You can show solidarity with Trenton and the other folks incarcerated at Lansing under unlivable conditions by emailing KDOC and Secretary of Corrections Jeff Zmuda to show support for these demands.

Email addresses: KDOC_Pub@ks.gov, nancy.burghart@ks.gov, Kristin.Finlay@ks.gov

We’ve started an email template for you to make it even easier to show solidarity—but the more you personalize it, the more likely it is to make it straight into an inbox rather than being sorted into spam! Find the template here or click below to send an email!

Demands of Restrictive Housing Residents at Lansing Correctional Facility

Transparency

We demand weekly written updates, signed by KDOC Secretary Jeff Zmuda and acting Warden James Skidmore, informing residents in restrictive housing of any policy and procedural changes.

Accurate classification

We demand an immediate review of official prison classification for inmates in Restrictive Housing, and immediate revision of false classifications. During the last several months, residents in protective custody have been mysteriously re-classified as OSR (Other Security Risk). This classification implies a different set of rules and restrictions than protective custody, and allows the KDOC to enforce stricter conditions and withhold resources based on a false classification. Those in Restrictive Housing must be correctly classified. The false classification not only prevents inmates from receiving resources and freedoms that should be available to them, but misidentifies them on official prison records that might be used in current or future legal action.

Movement/Day Room

We demand opportunities for movement and fresh air. One direct result of OSR re-classification is that it allows Unit Team Managers (UTMs) to restrict movement based on a non-existent security risk. We have been given no opportunities for exercise or fresh air, which causes both mental and physical strain that leads to unsafe conditions. It’s been six months with no fresh air!

Canteen

We demand regular access to canteen items and Union Supply Boxes in compliance with individual inmate incentive levels. Inmates in protective custody have not been able to order canteen for 10 months and have been denied access to their regular canteen orders. KDOC has made a variety of excuses for this, but inmates in protective custody have a right to canteen in accordance with Internal Management Policy and Procedures (IMPP) 11-101A, section V, and that right must be facilitated by administration.

Regular hygiene pack and blanket deliveries

We demand that you issue a notice to all corrections officers statewide that these essential items such as these cannot be withheld from inmates for any reason whatsoever, and that items must be delivered to indigent detainees at regular and predictable intervals. We demand that KDOC enact a set of disciplinary measures for any officers or prison staff that withholds essential items. Hygiene is a basic right pursuant to IMPP 12-127 and during the cold months, it is crucial that all inmates be supplied with cold- weather clothing as well as ample blankets and pillows in accordance with IMPP 12-129D.

Regular opportunities to receive public comment from family members

We demand that KDOC creates a structured system to hear and respond to concerned family members. While KDOC claims that they want to hear from the families of those incarcerated in Kansas prisons, they do not respond to phone calls or emails, and often belittle family members asking for basic information about their loved ones.

Important Terms and Concepts Explained

Following definitions can be found in IMPP 20-105A

Restrictive Housing

A generic term used to describe housing which separates residents from the general population for both administrative and disciplinary purposes.

Administrative Restrictive Housing

A form of restrictive housing used for residents who pose a threat to life, property, self, staff, or other residents; or when a resident’s continued presence threatens the secure and orderly operation of the facility.

Disciplinary Restrictive Housing

A form of restrictive housing to which a resident can be sentenced following conviction of a rule violation through disciplinary proceedings.

Protective Custody

Pursuant to IMPP 20-108 [Protective custody] any resident who requests restrictive housing for personal safety, or who the Warden has reason to believe to be in serious and imminent danger, may be placed in administrative restrictive housing if:

Documentation that protective custody is warranted is provided in writing by the Warden and reasonable alternatives are not available.

A denial of protective custody is to be fully documented in the EAI file.

Other security risk

The Warden may place in administrative restrictive housing, or secure confinement in the resident’s own cell, any resident or group of residents, if the resident or residents have engaged in behavior which has threatened the maintenance, security or control of the correctional facility.

The Warden is to, within three (3) working days of the placement, explain in writing the threat to security and show justification for effecting secure confinement under these circumstances to the Deputy Secretary of Facility Management.

An exception to the extended planning and services required under longterm restrictive housing placements may be requested with supporting written justification by the Warden.

A copy of this explanation and justification shall be provided to the Secretary of Corrections.

Follow Liberation Literature for more updates as the situation unfolds.